What emotion am I really feeling?

On noticing and naming your particular feelings — aka, emotional granularity

Hello, dear friends,

What emotions will you feel today?

Will you notice them? Will you call them out by name?

Why does that even matter?

This is one of the gems that surprised me in learning more about emotions.

It does apparently matter if we can notice and name our emotions. It matters to our health. Why?

Because emotions are created by us.

As neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett, PhD, said in an interview:

“It feels to us like emotions happen to us. Like we are basically the victims of circuits that trigger and that hijack us and cause us to do and say and feel things that we would rather not. But actually, your brain is making emotions on the spot as you feel them.

If emotions are made by us, we can learn to change what emotions we create!

How?

You can gain flexibility over your emotions, says Dr. Barrett, by training “your brain to learn different emotion words, to learn different emotion concepts, to basically become an emotion expert. And when you do that, what happens is that your brain makes emotional instances that are very very tailored to the specific situation that you’re in.”

“That’s actually really good for you,” she emphasizes.

(Listen to Dr. Barrett’s long and fascinating conversation with Adam Grant:)

What? Please give me an example!

Well, let’s think about feeling MAD.

Anger is one of the 3 emotions Dr. Brené Brown says most people can label.

Is it really anger?

Or is it shame? Embarrassment? Resentment? Irritation? Why?

There’s so much instant brain judgment going on in each emotion..

Your brain is processing at lightning speed a stimuli, past experience, your context in the world, and your expectations, and then manufacturing an emotion (presumably to protect you) before you might even notice what is happening.

But then: Why are you mad? Who are you mad at? What are you really feeling? What thought is at the root of your anger? How does that make you feel? Is there another option? (This line of wondering is similar to Bryon Katie’s fantastic 4 Questions.)

Here’s a made-up example.

I’m so MAD. Why am I MAD?

You might think…

“I am feeling resentful because I told them over and over again what time to show up and they aren’t here again. They are so rude! I can’t stand this! I’m furious!”

Anger often masquades as pain.

So if you know that, you might think ….

“I am actually also feeling very hurt. Because it feels like they don’t value my time. It feels like they don’t value … me.”

Oof. There’s a driving thought under it all. There’s a lot there, probably, about your history with this person and your own background. A lot your brain pulled into context.

“And if that’s true, it’s really upsetting. It makes me question my own worth, too.”

“It makes me feel despair and uncertainty.”

And then what to do?

“I realize I should talk to them about it, but what if they don’t want to hear it? Or dismiss me? I’m scared of that conversation.”

And then what?

“Am I willing to let go of this relationship? I feel so sad about that idea. I really don’t want to lose them.”

What are other options?

“Can I accept that they are just going to be late? Would that be OK with me? I haven’t considered that. How do other people handle this? Are they late for everyone?”

And maybe there’s a new thought that emerges ….

“Maybe it really is hard to get places on time right now. They do have a sick parent and three young kids. They are working two jobs. Maybe I should be checking on them instaed of getting mad. Oh, dear. Now I’m feeling sympathy and concern. Now I want to call them and find out how they are REALLY doing.”

This is all made up, but you can imagine, if you start digging into why your brain made up THIS emotion at THIS time, you’ll find an epiphany or two.

Emotions are rarely only about what is happening at that moment. They are a complex equation, of how you see the world, your expectations for what should be happening now, and what you have felt and processed and understood in the past.

OK, so what do I call my emotion?

Sociologist Brené Brown and her research team surveyed thousands of people and discovered that, on average, people can identify just three emotions while they are experiencing them: happy, sad, and angry.

Brené calls this the mad, sad, glad trilogy.

How can we look at our emotion more specifically?

One piece is noticing our emotion.

The other piece is practicing using a more expansive vocabulary.

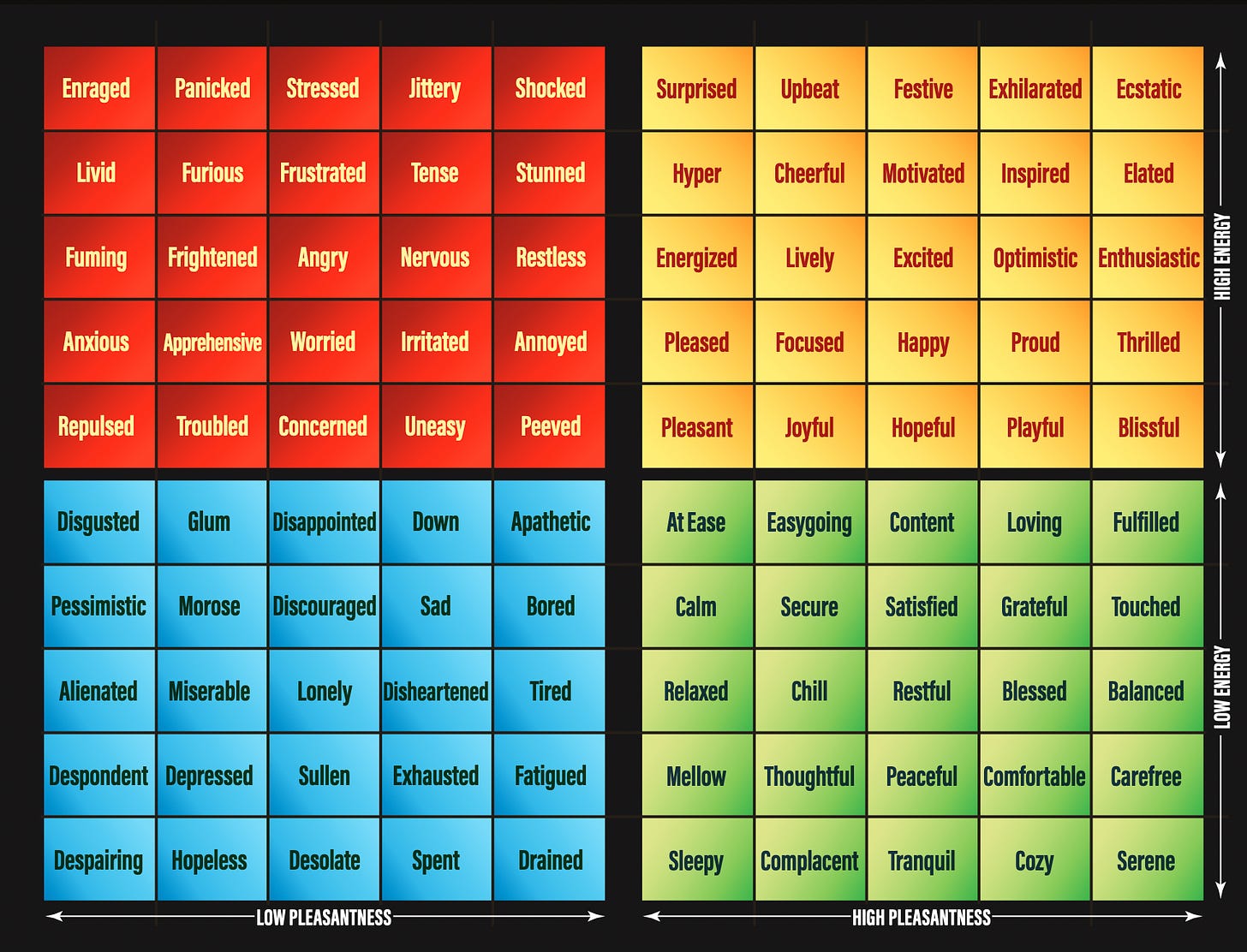

Kids are learning this now! My son brought a chart home from school, below, from researcher Marc Brackett’s terrific book Permission to Feel:

The quadrants are divided by two axes: low to high energy and low to high pleasantness.

For example, if you are feeling pleasant, hyper, or excited, you would be in the high energy and high pleasantness realms— in the yellow quadrant above.

If you are feeling morose, disgusted, or exhausted, you would be in the low energy and low pleasantness blue quadrant. And so on.

Look at all the different names!

Are you feeling sleepy, cozy, chill, or secure?

Are you feeling desolate, spent, glum, or tired?

Are you feeling playful, proud, motivated, or upbeat?

“Emotions are not reactions to the world; they are your construction of the world.” — neuroscientist Dr. Lisa Feldman Barrett

That happens when we lump more nuanced emotions all together.

Dr. Barrett calls this our “emotional granularity.”

More terms for emotions:

87 emotions and experiences — Brené Brown

How do you react, what happens, when you believe that thought? — Bryon Katie.

How emotions tie to our health

In her book, Atlas of the Heart, Dr. Brené Brown quotes German philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein: “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”

She elaborates in an interview: “Language doesn’t just communicate emotions; it shapes them. So when I use a word to describe how I’m feeling, my body will often follow my language. If I use hyperbole and go from saying, ‘I’m stressed’ to ‘I’m overwhelmed,’ often I make that a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Emotions can set off our body’s stress response.

If we feel furious at someone, that has real physical ramifications for our body.

If we feel angry or on edge all day long, that keeps our body in a state of a stress response. When we feel chronic stress, that can put a toll on our health.

Describing specific emotions can help you separate yourself from your brain’s manufactured feeling and look more closely at what is happening.

Describing specific emotions can allow you to practice being curious rather than running with the first emotion your brain hands you.

Describing specific emotions can help you feel calmer and more in control.

If you try noticing and naming your emotions, let us know how it goes!

To our journeys,

Brianne

p.s. This is the second post about emotions. Read the first post here.

Emotion: "just electrical activity in my head"

Hi, dear friends, Our whole emotional world can sometimes seem shaped by forces out of our control. It might seem that emotions are like the weather. Sure, we have some sense of what’s coming based on the patterns, the El Niños of our lives — Christmas joy, tax stress, annual health scan uncertainty — but also, in any given afternoon, surprise showers and drops in temperature.

This was so, so well done and is such important messaging. If we can’t name complex emotions, they’re certain to get ‘stuck’ in our bodies somewhere.

You’ll probably enjoy Susan David’s work too. Emotional agility. She was interviewed by Adam Grant the week after Lisa Feldman Barrett

https://open.spotify.com/episode/4TpUmGWSdRwAqUeMYUfLQu?si=Z7wRaAjxQDSIjQOjy81XMQ I originally came to her when Brené Brown interviewed her on Dare to Lead

https://brenebrown.com/podcast/brene-with-dr-susan-david-on-the-dangers-of-toxic-positivity-part-1-of-2/. Toxic positivity is only a part of her message, and she prefers to call it ‘forced positivity’ these days.