Hello, dear friends,

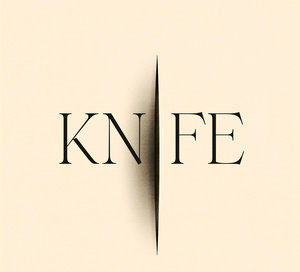

“Knife” is a memoir by the acclaimed writer Salman Rushdie, written after he was attacked by an assailant with a knife in 2022 in western New York. I picked it up on a whim from the library shelf. I’m not sure what I expected — perhaps an intellectual and dense nightmare — but this book was not that. Instead, the chronicle is personal, reflective, strewn with philosophical threads about healing and self.

“Knife” is about more than an attack with a knife. It is about a human moving through to the other side of a horrific and traumatic experience, grappling with uncertainty, identity, questions, perspective, and feeling their way forward.

As he writes in the first page, Salman was on stage on that August evening to talk about the importance of keeping writers safe in America. He is a long-time expert on this topic because, in 1989, after the publication of his novel “The Satanic Verses,” the Supreme Leader of Iran had issued a fatwa, an order to his followers to kill the author. For years, Salman had heavy security; then he moved from London to New York City and decided, resolutely, to simply begin living his life — dining out, strolling the streets, letting people see him and get over the idea of an imminent threat. He had moved on — until this young man (who had reportedly been radicalized by online videos) showed up.

A vicious attack is different from a serious illness, and yet, there are similarities. Major illnesses too begin with an attack of some sort — by a virus, by a bacteria, by an unruly cancer cell, by one’s own immune system gone awry. And both are often followed by a shock, a re-evaluation of the safety of the world, an identity shift, and a thick fog of processing to wade through.

Identity

The quote on the opening page:

We are the other; no longer what we were

before the calamity of yesterday

— Samuel Beckett

How do we see ourselves? How do we understand who who we are? How do others see us and understand us?

The surface holds the most obvious transformation. An attack or an illness can change our physical appearance — we can abruptly appear as a stranger even to ourselves. Salman’s wife, the poet Rachel Eliza Griffiths, filmed Salman throughout his recovery, capturing his appearance and his train of thoughts. He told her, “I look like someone else.”

And it was more than that.

Salman writes:

“The most upsetting thing about the attack is that it has turned me once again into somebody I have tried very hard not to be. For more than thirty years I have refused to be defined by the fatwa and insisted on being seen as the author of my books—five before the fatwa and sixteen after it. I had just about managed it. When the last few books were published, people finally stopped asking me about the attack on The Satanic Verses and its author. And now here I am, dragged back into that unwanted subject. I think now I’ll never be able to escape it. No matter what I’ve already written or may now write. I’ll always be the guy who got knifed. The knife defines me. I’ll fight a battle against it, but I suspect I will lose.”

It is not the same, but it reminded me of how an illness can remake how people see you — or perhaps, more to the heart, how you think people think of you, whether or not you are correct. And it’s often outside of your control — you have lost the ability to lead the narrative.

Rehabilitating yourself in another reality

As his condition improves, Salman moves from a medical center in Pennsylvania to Rusk Rehabilitation in New York City. At one point, he is in the hospital bathroom, staring at his distorted reflection in the mirror. He has lost use of an eye; that eyelid is stitched shut temporarily. His face is scarred; a cut mars the left corner of his mouth.

He muses:

“There is the rehab of the body, but there is also the rehab of the mind and spirit. When I left my family home for London, it was the first time I passed through the looking-glass and had to rediscover and remake—rehabilitate—myself in another reality, and play a new role in a new world. After the Khomeini fatwa, I had to do it again. When I left London for New York, it was the third time. And this, now, here at Rusk, was the fourth.”

“Are you okay in there?” the nurse wants to know.

“Yes. I just need some time.”

“No rush. Pull the cord when you’re done.”

We all need time. Time to remake ourselves in a new reality.

Processing an experience

At another point, Salman is visited in the hospital by his agent, Andrew Wylie. Salman recounts:

“I don’t know if I can write again,” I told him.

“You shouldn’t think about doing anything for a year,” he said, “except getting better.”

“That’s good advice,” I said.

“But eventually you’ll write about this, of course.”

“I don’t know,” I replied. “I’m not sure I want to.”

“You’ll write about,” he said.

It was as if there was no choice.

Salman’s wife, the poet Rachel Eliza Griffiths, notes, in an arresting recap of the event from her point of view, “writing is how my husband breathes.”

While Salman is an amazing and prolific author, processing an intense experience through words is something any of us can do. It can be healing. It can be helpful. It doesn’t need to be a book.

Working through words could mean speaking to a friend or a therapist. It could mean free-writing. It could mean responding to prompts.

In the latter part of the book, Salman begins imagining a dialogue with his assailant.

In his imagination, they meet, in four sessions. Salman questions him and circles his refusals to engage, a sparing that is alternately frustrating, funny, and infuriating.

It made me wonder — what would it be like to imagine a dialogue with a tumor? Or a bacteria? Or some other instigator of bodily disaster?

I don’t think I could do it.

Three things

Toward the end of his memoir, Salman shares “three things had happened that had helped me on my journey toward coming to terms with what had happened.”

“The first was the passage of time. Time might not heal all wounds, but it deadened the pain, and the nightmares went away.”

The second was therapy.

“And the third was the writing of this book. These things did not give me ‘closure,’ whatever that was, if it was even possible to find such a thing, but they did mean that the assault weighed less heavily on me before.”

Therapy and writing are useful tools all around. And the passage of time is coming for each of us regardless.

Time can deaden the pain not because the body heals entirely and returns to the time-before — an impossible dream — but because we learn how to work around the change, accept it, and cope in new ways as time slips on.

We are changed, and we are still ourselves, too.

To our journeys,

Brianne