Field Notes #21: Mask paradox, understanding pain, “Epigenetic” poem by Rebecca Sturgeon

On how masks work but mask mandates work, and a new book on pain, “The Song of Our Scars”

Hello friends, and Happy Wednesday! Welcome back to Field Notes, the edition of Odyssey of the Body that comes out every Wednesday with 2-4 things I’ve run across lately. The Sunday edition, which is an essay-ish piece, is on hold during a busy conference-gala season at work and Little League baseball season at home. I’ve found it surprisingly comforting to acknowledge the quirks of a year and make deliberate adjustments by season, rather than attempt to go the same constant speed. It feels proactive, easier, and expansive to give things up on purpose, rather than reactive, harder, and restrictive to miss things accidentally because too much is trying to fit into 24 hours. What is happening this season? Where do I want to put more of my energy and attention? Where can I do less? This method also ends up encouraging me to savor this season and anticipate the next. What season are you in? How are you adjusting?

1} Masks work — but mask mandates don’t?

We are on the eve of the gala at my work, which will be in person for the first time since 2019. (This email is a personal project, separate from my job, but I’ll sometimes share things I’ve run across there). The gala is in New York City, which is on a high alert level. There is currently no mask mandate, though the Commissioner of Health has put out an advisory recommending masks at indoor gatherings.

I wondered why there was no mask mandate, but then I read this fascinating piece (That’s a gift link; it should be open to you.) by David Leonhardt.

It turns out that masks work, but mask mandates don’t.

He writes:

From the beginning of the pandemic, there has been a paradox involving masks. As Dr. Shira Doron, an epidemiologist at Tufts Medical Center, puts it, “It is simultaneously true that masks work and mask mandates do not work.”

To start with the first half of the paradox: Masks reduce the spread of the Covid virus by preventing virus particles from traveling from one person’s nose or mouth into the air and infecting another person. Laboratory studies have repeatedly demonstrated the effect.

Given this, you would think that communities where mask-wearing has been more common would have had many fewer Covid infections. But that hasn’t been the case.

In U.S. cities where mask use has been more common, Covid has spread at a similar rate as in mask-resistant cities. Mask mandates in schools also seem to have done little to reduce the spread. Hong Kong, despite almost universal mask-wearing, recently endured one of the world’s worst Covid outbreaks.

Why is this?

Some speculate that the virus is so contagious that any bit of non-mask wearing — say, taking it off to eat, or letting it slide under your nose — means the virus keeps spreading. The mask helps protect in the any given moment, but when the virus is pervasive, it is going to find any holes in the system.

The main explanation seems to be that the exceptions often end up mattering more than the rule. The Covid virus is so contagious that it can spread during brief times when people take off their masks, even when a mandate is in place.

Airplane passengers remove their masks to have a drink. Restaurant patrons go maskless as soon as they walk in the door. Schoolchildren let their masks slide down their faces. So do adults: Research by the University of Minnesota suggests that between 25 percent and 30 percent of Americans consistently wear their masks below their nose.

2} Understanding pain

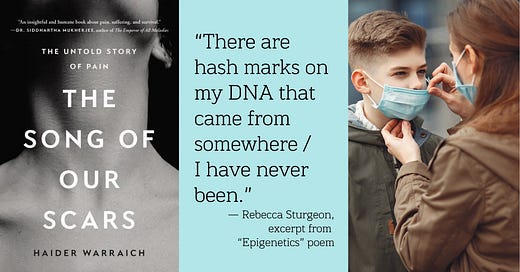

I’m reading The Song of Our Scars: The Untold Story of Pain by Haider Warraich in my preparation for the Gold Foundation’s annual Summer Reading List of Compassionate Clinicians. (That’s the 2021 list. The 2022 list is in progress! If you have any recommendations, I’d love to hear. Books have to have been published since the last list came out.)

So far, it’s one of those unusual books that sprinkles poetic lines beside medical studies and a probing of the human condition.

It begins: “Pain is a fundamental truth. … Pain is one of the most consistent aspects of the consensus reality we all experience, a hallmark of consciousness among all beings, hardwired into our frames through evolutionary mechanisms millions of years in the making.”

Here are two explanatory sections at the beginning that, for me, added up to a keener understanding of “pain”:

“In reality, pain is one of three distinct but overlapping phenomena. On one end of the spectrum is something called nociception. Nociception, the process through which potentially injurious stimulation is detected and transmitted by our nervous system, is often confused with pain. Nociception is a purely physical sensation, shared by all living things, even cells and plants.”

Suffering, Dr. Warraich writes, is on the other end. Pain exists between the two.

“For nociception to transform into pain, the organism needs to possess the ability to feel something, recognize it as noxious, assign a negative connotation to it, physically withdraw to avoid it, and learn to avoid it in the future. This transformation happens not in the skin but in our brains. Pain is in essence the conscious manifestation of nociception.”

This explanation made me think of how toddlers sometimes will stumble and fall hard, and then look up to gauge the reaction of those around them. Should I wail? Or keep on going to get that toy? I wonder if their brains are trying to figure out, in some way from the cues around them, How much pain should I be feeling?

It’s all rather fascinating, and I’m looking forward to reading the second half of the book.

3} “Epigenetic” Poem

One of my favorite newsletters is Our Daily Breath, a tiny draft of poem that arrives Wednesday through Friday from poet Rebecca Sturgeon. It’s short enough to gulp in one quick, delicious reading. It reminds me each time that poetry does not have to be hard, opaque, aloof, but can be easy, tactile, wondrous.

Here’s a favorite poem, which Rebecca introduced in this way:

I have been thinking about inheritance, epigenetics, and the fact that the egg that became me existed inside my mother’s ovaries when she was a fetus inside her mother’s body. We were nested dolls. This blows my mind, and is also oddly comforting.

Epigenetic

By Rebecca Sturgeon

There are hash marks on my DNA that came from somewhere I have never been. I was the innermost nested doll in my grandmother's uterus, learning before the possibility of my birth lessons of generations I would never know. This is the reason, sometimes, when I turn a dark corner and nothing is there voices in my genes whisper secrets to my aging cells

You can subscribe to Our Daily Breath here.

I hope you have a deliberate, expansive, and healthy week ahead.

To our journeys,

Brianne